Culture

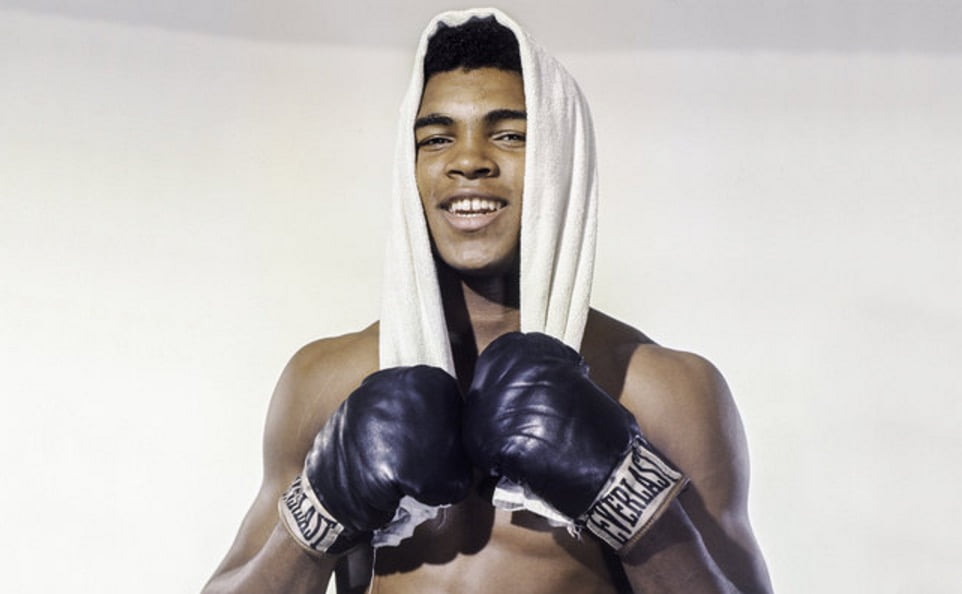

How Muhammad Ali Affected This Blog

I have sort of strangely been wanting to write about Muhammad Ali’s death all weekend. As I bobbed and weaved through Memorial coverage, Oklahoma State’s regional romp over Clemson and Kyle Boone’s excellent OSU recruiting coverage, his passing continued to linger in the back of my mind.

I wasn’t totally sure why. Was it because one of my first great sports memories was him lighting the torch in Atlanta at the ’96 Games? Or was it because he stood for something (whether you agreed with him or not) when athletes won’t take a stand on anything these days (gotta sell shoes!), something that might literally get LeBron or Cam Newton crucified in 2016? Or was it because he is arguably the greatest athlete in sports history?

It might be all of those things, I suppose, but my moral heroes have never really been athletes and I never really engaged his career because it was long over before I was born. So I think the reason Ali’s death weighed on me has less to do with him as a person and more with how he affected sportswriting. Maybe even my sportswriting … this blog.

Bryan Curtis wrote about this for the Ringer on Saturday.

Once, the old Newark Star-Ledger columnist Jerry Izenberg tried to explain to me how Ali had changed the men who covered him. “He gave us a reason to become what we wanted to become,” Izenberg said.

And it was what a writer named Mark Kram wanted to be that may have affected my career more than anything else I’ve ever read. His gamer on Ali-Frazier 3 — The Thrilla In Manila — is likely the greatest sports story I’ve ever read. Maybe not in subject matter. Maybe not in content. But for the pure writing of the thing, my gosh.

I can’t remember when I first read it, but I know I’ve come to it over and over again in the last five years. I hate reading anything twice. I’ve read this story about 15 times. Here’s how it starts. This is how it starts!

“Man, I hit him with punches that’d bring down the walls of a city,” said Frazier. “Lawdy, Lawdy, he’s a great champion.” Then he put his head back down on the pillow, and soon there was only the heavy breathing of a deep sleep slapping like big waves against the silence.

It somehow gets a lot better from there although that “walls of a city” quote is the one that endures. Kram was there in Manila and wrote for SI some of the most beautiful copy I’ve ever seen about that famous fight. Look at this.

True to his plan, arrogant and contemptuous of an opponent’s worth as never before, Ali opened the fight flat-footed in the center of the ring, his hands whipping out and back like the pistons of an enormous and magnificent engine.

Much broader than he has ever been, the look of swift destruction defined by his every move, Ali seemed indestructible. Once, so long ago, he had been a splendidly plumed bird who wrote on the wind a singular kind of poetry of the body, but now he was down to earth, brought down by the changing shape of his body, by a sense of his own vulnerability, and by the years of excess. Dancing was for a ballroom; the ugly hunt was on. Head up and unprotected, Frazier stayed in the mouth of the cannon, and the big gun roared again and again.

That is some outrageous writing, but it’s not my favorite part of the whole thing. That came next.

Coach Glass had this quote put up in both of our #okstate weight rooms. #RIPMuhammadAli pic.twitter.com/UiPb3Hk1i3

— Gary Calcagno (@calcagnogary) June 4, 2016

Came the sixth, and here it was, that one special moment that you always look for when Joe Frazier is in a fight. Most of his fights have shown this: you can go so far into that desolate and dark place where the heart of Frazier pounds, you can waste his perimeters, you can see his head hanging in the public square, may even believe that you have him, but then suddenly you learn that you have not.

Once more the pattern emerged as Frazier loosed all of the fury, all that has made him a brilliant heavyweight. He was in close now, fighting off Ali’s chest, the place where he has to be. His old calling card—that sudden evil, his left hook—was working the head of Ali. Two hooks ripped with slaughterhouse finality at Ali’s jaw, causing Imelda Marcos to look down at her feet, and the President to wince as if a knife had been stuck in his back. Ali’s legs seemed to search for the floor. He was in serious trouble, and he knew that he was in no-man’s-land.

Breathtaking. The end is incredible too. Words and sentence I aspire to write.

This is what world class athletes do to you though. They bring something out of you. I don’t know why and I don’t know how, but they stir the thing inside of you that wants to be stirred and then you just start pouring it out. I’ve experienced this to a much lesser degree with guys like Markel Brown, Brandon Weeden, Rory McIlroy and Jordan Spieth.

I’m not sure anybody did it like Ali though. Swaggy, brash and elite, he might not have changed sports and he might not have changed culture (although he might have), but it’s hard to deny he didn’t change sportswriting.

He gave us a reason to become what we wanted to become.

It’s not his only legacy. But it’s a great one.

-

Football3 days ago

Football3 days agoFour-Star Quarterback Adam Schobel Commits to Oklahoma State, Flips from Baylor

-

Hoops3 days ago

Hoops3 days ago‘Keep Turning Over the Rocks’: Looking at the Portal Landscape as Lutz Looks to Solidify His First OSU Roster

-

Hoops3 days ago

Hoops3 days agoFour-Star Signee Jeremiah Johnson Reaffirms Commitment to Oklahoma State after Coaching Change

-

Daily Bullets2 days ago

Daily Bullets2 days agoDaily Bullets (Apr. 23): Pokes Land Four-Star Quarterback, Retain Talent from Mike Boynton Era